Wimbledon, Day 5: Goodbye Andy Murray

A tribute to England's most winning player in the Open Era, while a grand dame of English tennis and a Civil Rights hero continues to be overlooked.

Wimbledon, Day 5, was all about the Brits. Correction: it was all about Andy Murray.

No one could remember a bigger crowd for a men’s first round doubles match, on Centre Court, no less — the last time that happened was 1996 when “the Woodies” (Australians Todd Woodbridge and Mark Woodforde one of the most successful pairings in tennis history) took on Ken Flach and Robert Seguso. Brothers Murray, (Jamie and Andy) — cameramen practically in their faces — radiated with tension as they walked out and the cheers went up, but consummate professionals, eased into their warm-up routine.

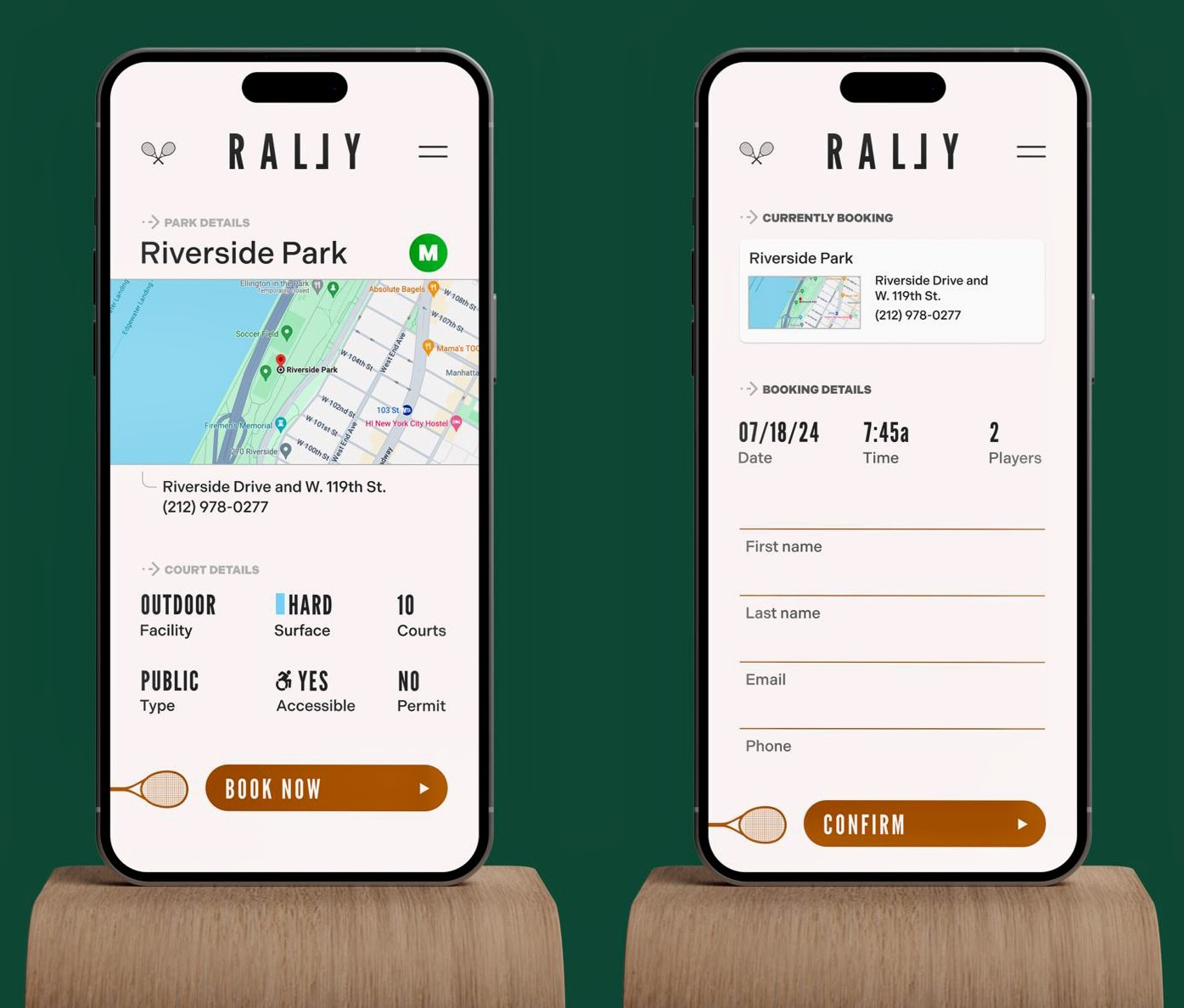

Launching soon: RALLY, an AI-powered, digital-first platform for all things tennis and racquet sports, enables local players and city transplants to find courts/clubs, renew permits/memberships, hire coaches/professional hitters, and participate in competitive and community-driven activities. www.rallytheapp.com

The tributes for brother Andy Murray, long overshadowing brother Jamie — seven-time doubles champion (five in mixed doubles and two in men's doubles), a Davis Cup winner, and a former doubles No. 1 — almost lasted as long as the match. After three games, Andy clutched his back; at the change of ends, he sat down with a grimace. Despite a roar by Jamie, Brothers Murray lost the first set in a tiebreak; Jamie took the blame losing two mini-break points. The second set went service break to service break.

The tributes for brother Andy Murray, long overshadowing older brother Jamie — seven-time doubles champion (five in mixed doubles and two in men's doubles), a Davis Cup winner, and a former doubles No. 1 — almost lasted as long as the match. After three games, Andy clutched his back; at the change of ends, he sat down with a grimace. Brothers Murray lost the first set in a tiebreak; Jamie took the blame losing two mini-break points. The second set went service-break-to-service-break, but a 2-0 lead with a return and a frustrated/motivated/mammalian from Andy soon faded and Brothers Murray lost the match 6-7, 6-4.

Cue retired broadcaster Sue Barker. Cue the Jumbotron. As Andy watched, a showreel featuring tributes from Roger Federer, Novak Djokovic (who is still competing and turned up at Centre after the match) Serena Williams, and Rafael Nadal was played as the whole Murray family cried, including mum, Judy (of course), wife, Kim, dad, Willie, and two of his four children. Everyone was so caught up in the moment, no one seemingly noticed the musical choice: a Scala & Kolacny Brothers Belgian girls' choir, version of Radiohead’s Creep conducted by Stijn Kolacny and accompanied by Steven Kolacny on the piano (sans the chorus and the bad words.)

“When you were here before/Couldn't look you in the eye/You're just like an angel/Your skin makes me cry,” according to the lyrics. “You float like a feather/In a beautiful world/I wish I was special/You're so fuckin’ special

”[Chorus] But I'm a creep, I'm a weirdo/What the hell am I doing here?/I don't belong here.”

While the videos and eulogies for Murray’s career roll in, however, (he still has the mixed doubles to play) another British player has gone overlooked for years. Angela Buxton, a doubles champion (with Black player Althea Gibson), singles finalist and Civil Rights activist in the 1950s never received an honorary membership at the All-England Lawn Tennis Club (AELTC), the host club of Wimbledon, neither while she was alive or posthumously. She was neither memorialised with a statue nor a scholarship, an induction into the International Tennis Hall of Fame (ITHF) in Rhode Island nor a special exhibit in any Jewish Museum, aside from the National Jewish Sports Hall of Fame and the Black Tennis Hall of Fame, “for her for her doubles partnership… as well as her efforts to raise funds for the ailing Gibson near the end of her life.”

Other Jewish players, including American Wimbledon champion Dick Savitt, have become members, and there is some confusion surrounding Buxton’s application to the club. Still, the fact that a Jewish woman who did more than practically anyone else to support the integration of tennis and the recognition of Black tennis players, especially women, remains a serious oversight, according to many historians. “Not inviting Angela Buxton to become a member of the All England Club in 1956 was a startling omission by the Club,” said David Berry, the author of A People’s History of Tennis. “It was true that only singles champions are automatically given honorary membership of the Club. But that year Angela had won the doubles… and lost in the singles final to Althea. This was the best achievement by a British woman for many decades and surely merited being offered membership.”

Angela Buxton, born in Liverpool in 1934 to Violet (Greenberg) Buxton and Harry Buxton, a nascent entertainment mogul, spent her formative years (1940-1945) in Cape Town and then, Johannesburg, South Africa, where she was often reprimanded for playing with the children of Black servants — colour barriers had never crossed her mind, she once said. When the war ended in 1945 and the Buxtons returned to England, they settled in Hampstead, where Buxton trained under Bill Blake at the Cumberland Club, the best club in North London. Angela felt she was a shoo-in for membership. “(Bill) welcomed this young player who seemed to have some promise, and after a few lessons, gave her an application to join the club,” according to the 2004 book The Match: Althea Gibson & Angela Buxton : How Two Outsiders — One Black, the Other Jewish — Forged a Friendship and Made Sports History by Bruce Schoenfeld. “She filled it out: name, address, parents’ name, religion, all the details. Weeks passed and nobody mentioned her status…“Each time she stepped inside the club… she inquired about the application… Finally, Bill Blake couldn’t stand it any longer. ‘Look, Angela, please don’t keep asking me, you’re not going to be able to join the club,’ Blake told her.” When she asked why not, he replied, “‘No, you’re perfectly good, but you’re Jewish.’”

Gibson and Buxton were soul sisters, born in prejudice. As soon as Buxton saw Gibson during Gibson’s 1951 British debut at The Queen’s Club, she knew she had seen the future. “The British weren’t particularly taken with Althea, either,” Schoenfeld wrote, “she seemed arrogant in her conversations with other players, tight-lipped and… quick to take offense.” In the early 1950s, Gibson had hit a slump and almost gave up tennis to join the Women’s Auxiliary Army. But a U.S. goodwill tour of Southeast Asia and an acquaintance with Buxton changed the course of history. Buxton, who was there for the Wightman Cup, an annual US vs. UK women’s team tennis competition, began practicing with Gibson and before the trip was through “Angela had convinced Althea to travel to Europe.”

From then, until Buxton’s retirement in 1956 due to tenosynovitis, an incurable wrist inflammation, and Gibson’s in 1958, the two were not only doubles champions and practice partners, but moral supports, cinema buddies, golfing mates and in the case of Buxton, occasional patron. Whenever Gibson came to play in England, she stayed at Rossmore Court (Buxton’s apartment near Regents Park), and Buxton, a designer for Lillywhite’s sporting goods store, helped dress Gibson for her subsequent grass court appearances at Queen’s, in Bournemouth and during her 1958 Wimbledon championship.

After retirement, Buxton formed the Angela Buxton Tennis Academy in North London with her former coach, Clarence Medleycott “Jimmy” Jones, a newspaperman, tennis magazine founder and until the end of his life, companion. After Jones and her son, Joseph (a LTA chair umpire) died of HIV, she permanently moved to Florida, continued her coaching, while also sponsoring young players competing at America’s Orange Bowl. In the scattered months following her 1956 Wimbledon accomplishments, Angela had been advised to “strike while the iron is hot,” for Wimbledon membership because “you may never get the chance again,” Buxton told Schoenfeld. While singles winners automatically become members — and still do to this day — winners of the Gentlemen’s Ladies’ and Mixed Doubles must submit applications. Angela did as told, but never received a response. She thought about it occasionally through the years, according to The Match, but she wasn’t planning on taking a journey to SW19 just to play tennis. But her lack of membership started to resonate among her pupils and peers. In 2019, a reporter from the Times came to inquire about it, and she willingly told him, “I suppose it’s because I’m Jewish,” which made headlines. Wimbledon had a few Jewish members by then, but none as forthright or as prominent as Buxton. In time, the AELTC informed Buxton that she must have declined and that she would have to return to the waiting list. “That’s all right, I’ve only been waiting thirty years,” Buxton said. Buxton died in Fort Lauderdale, Florida in August 2020.

“A couple of years ago, a ‘friend’ of the All England Club invited me to an off the record briefing about the ‘real reason’ Angela was never offered membership hinting at some aspects of her character that were not in keeping with the club,” Berry said. “Certainly, she could be a difficult woman at times — but then so could many other top champions. I declined the briefing on the basis that it is too easy to make character aspersions without anyone taking responsibility for them.

“Now of course we will never know unless the All England Club finally decides to talk about the matter openly, about as likely as a British woman in this year’s Wimbledon championships coming anywhere near emulating Angela’s amazing achievement in 1956.”

Perhaps it bothered Buxton to the very end, perhaps not. In her later years, she was almost totally focused on the new generation of players. When in 1996, Buxton received an invitation from Richard Williams to meet his young daughter, Venus, Buxton asked for a phone and punched in Gibson’s numbers and the two Black trailblazers chatted. Eight months later, on the Eve of Venus’ run to the U.S. Open final, Gibson gave to Venus the same advice she had lived by and passed on to her lifelong doubles partner. “Be who you are and let your racquet do the talking,” she said. “The crowd will love you.”